The Devil’s Nectar: The Science Behind Alcohol

“Ah my Beloved, fill the Cup that clears

Today of past Regrets and future Fears.

Tomorrow? - Why, Tomorrow I may be

Myself with Yesterday’s Seven Thousand Years”

XX Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, 12th Century

Strange Brew

Alcohol is the most widely consumed psychotropic substance in the world. A cultural history of alcohol would fill a library and the scientific literature is similar in volume. In countries where alcohol is legal one is never too far away from a cold beer or other enticing beverage. Most adults have a pretty clear idea of the effects of alcohol. Yet, in getting to the bottom of fairly simple questions like what exactly alcohol does to the body, how does the body process it, or how much is okay to drink regularly before it starts damaging health, it can be quite hard to pin down precise answers.

Popular articles about alcohol tend to fall into three main types. Firstly, there is the simple ‘food and drink’ piece about the latest summer cocktail or best wine to pair with a beef Wellington which colourfully describes the flavours of a particular beverage but is somewhat coy about the key ingredient. Then there are the ‘Why I Gave Up Drinking’ confessionals in which the narrator describes a descent into dipsomania - hopefully with plenty of lurid detail - before an arduous climb to the sunny uplands of sobriety. More recently we have seen ‘this is what happened when I gave up alcohol’ piece in which the writer somewhat unsurprisingly reports better sleep, more energy, better skin and so on upon quitting drink. Then there is the third science-based ‘latest study’ type that promises to settle, once and for all, the question of whether moderate drinking is okay or bad for one’s health. The findings seem to change according to what day of the week it is and usually leave the reader none the wiser. To be fair on health reporters they have an uphill task picking apart the slew of conflicting research, and unlike personal stories which are relatable and easy to process, statistical data is tricky to get one’s head around. I for one am left groping for the drinks cabinet upon reading phrases like ‘Mendelian regression’ or ‘collider bias’.

Discussion about alcohol tends to be all-or-nothing; either booze-hell or sober-heaven, a habit which is either healthy or high-risk, and in Western culture there is often a slight whiff of morality when we talk about drink, as if - Heaven forbid - we should actually show people enjoying something without some consequence. Of the above mentioned types of article about alcohol, it is perhaps the food and drink ones which are the most useful: Not only are they guides on how to actually enjoy a drink, but they all implicitly contain a crucial piece of wisdom, backed by science, which we will come to shortly.

Alcohol: A Brief History

Alcohol, or ethanol, is a water soluble molecule that is most commonly produced in nature by fermented fruits. It is ingested by many species, including birds, bats, insects and apes, who primarily use it as a source of fuel (and possibly intoxicant). Its relevance to humans is that around 10 million years ago in pre-human hominids, there was a significant mutation in a gene that encodes an enzyme called ADH4 which is abundant in the upper GI tract (oesophagus, stomach and duodenum). This mutation resulted in a 40-fold increase in our ape-like ancestors’ capacity to metabolise alcohol and occurred around the same time that they were shifting down to terrestrial habitats. The upshot is that they were better able to tolerate ethanol in the fermented fruits abundant on the forest floor, which they could now use as an extra fuel source. This raises the interesting question of how far this new found ability to literally stomach alcohol contributed to our evolution to homo sapiens. In any case the fact that they were able to use fallen fruit as fuel was an important evolutionary bonus. Also, as no longer tree-dwelling their arms could be used for other things like manipulating tools etc. while they learned to walk on two legs, or stagger depending on the amount of ‘fruit’ they had consumed.

There is plenty of archaeological evidence of pre-historical alcohol use. In what is now the Middle East, the Natufian hunter-gatherers were brewing beer around 13000 BCE, while in Neolithic China around 7000 BCE beverages were being brewed from rice, honey and fruits. For the ancient Egyptians beer was a staple and there is compelling evidence that the Great Pyramids were constructed, not from alien technology, but good old-fashioned labour, with armies of workers supplied by vast canteens dishing out beer and beef-burgers (apparently). Wine was supped in Ancient Greece and Persia, including by the legendary mathematician Omar Khayyam whose famous poetry contains more than one mention of ‘The Grape’. In medieval Europe monks diversified as expert vintners and brewers and in Victorian Britain, before Bazalgette’s sewers revolutionised public health, it was far safer to drink ale than the London water, possibly accounting for the ubiquity of pubs in London.

Of course, for some cultures alcohol has been destructive. The white settlers in North America didn’t hesitate in encouraging alcohol use among the Native Americans, for whom alcohol remains a leading cause of premature death. Nor were these European immigrants immune. Jack London’s classic autobiography John Barleycorn: A Drinking Life, describes in vivid detail just how pickled many parts of the US were in the early 20th century, with bars and salons spilling out into every main street, and the widespread drunkenness - and no doubt fear about the productivity of the workforce - eventually culminating the policy of Prohibition. Throughout human history alcohol has been variously a fuel, a medicine, an intoxicant, a euphoriant, a ritual brew, a social lubricant, a culinary art and an agent of destruction.

The Physical and Mental Effects of Alcohol

The psychological and physical effects of alcohol are difficult to tell apart. Before the first drink touches our lips our brain is already releasing neurotransmitters like dopamine in anticipation. One of the characteristic features of alcohol dependency is ‘salience’ whereby an increasing proportion of one’s thoughts revolve around drink. For the drinker this can provoke all manner of emotions - shame, despair, anticipation, etc - yet is really, on an organic level, simply motivated by the nervous system seeking out alcohol to re-balance it. Likewise that vague sense of shame and guilt that often follows a big night out is, in the most part, due to imbalances in brain chemistry rather than any shocking behaviour the night before, or at least one hopes. Regardless of the varied mental, social and cultural effects of alcohol, the biological ‘mechanism of action’ is virtually the same for everyone.

Absorbtion

Once ingested, alcohol is absorbed in the lining of the upper GI tract and then processed via the liver before entering the rest of the body, via the systemic circulation. During its passage through the upper GI tract and liver it undergoes first pass metabolism (FPM) where, depending on conditions such as food in the stomach, as much as 25-50% of the alcohol is already processed before it even gets into the systemic circulation. The ethanol that makes it past FPM diffuses quickly through the bloodstream to the organs and tissues of the body, especially to those parts with a high blood supply relative to their mass, such as the liver, kidneys and brain. Alcohol is more slowly absorbed by muscle, though more muscle provides more ‘lean mass’ for distribution, leading to slower peak blood alcohol concentration (peak BAC). Alcohol is barely at all absorbed into fat. A slow peak BAC and faster elimination rate of alcohol is generally healthier with regards to alcohol consumption.

GABA and Glutamate

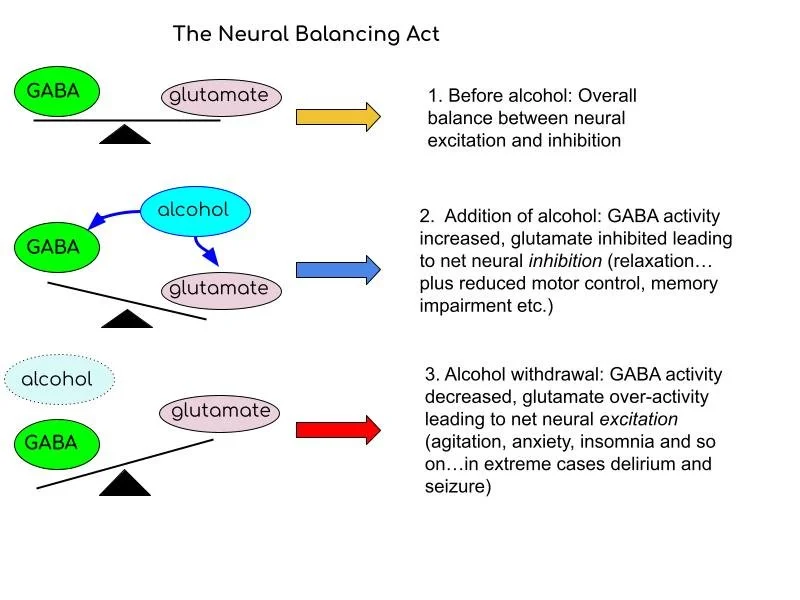

In the brain alcohol acts on a receptor abundant on the surface of neurons called the GABA-a receptor, normally activated by GABA (gamma amino butyric acid), the brain's major inhibitory neurotransmitter. Receptors can be thought of as doors on the cell surface, and neurotransmitters as keys, which allow certain molecules to flood into the cell, changing their activity. Alcohol both potentiates the GABA-a receptor, essentially supercharging it, and acts to release GABA itself, resulting in overall increased neural inhibition. Additionally, alcohol inhibits the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate (which acts on a receptor called NMDA), further relaxing the nervous system. It also promotes the release of dopamine and serotonin, accounting for its euphoric and addictive qualities.

However, a common feature of human biology is that what goes up must come down and vice versa. With repeat exposure the body down-regulates GABA-a receptors, making them sparser on the cell surface, and up-regulates NMDA receptors. In the absence of alcohol, say the following day after a night out, or if a chronic drinker decides to stop suddenly, this essentially results in too little GABA and too much glutamate activity, leading to overall neural excitation. Glutamate is important in thinking, memory and learning, but too much of it, and too little GABA, leads to the agitation and anxiety of alcohol withdrawal, and can even lead to delirium tremens, seizure and worse. Alcohol also depletes vitamin B stores, in particular B1, aka thiamine, and this in turn can result in a condition called Wernicke's encephalopathy, characterised by confusion, imbalance, memory-loss and potential brain damage (Korsakoff's syndrome). It is for this reason that heavy drinkers should never go cold-turkey, no matter how well-intentioned, and ought to take regular B-vitamins.

Heavy Vs Moderate

The majority of drinkers never reach this stage. The figures vary by country, but globally around 4% of all drinkers develop an alcohol use disorder (AUD) at some time - a lot of people, but still a minority. It’s not entirely clear why some people are more prone than others. Genetic predisposition, social factors, personal history, exposure to drink and so on all play a role, and quite unpredictably, to the extent that it is pointless to blame the heavy drinker for developing an addiction. In any case most drinkers avoid this. Even if they were pretty hedonistic in their youth, excessive alcohol use is normally staved off in most by a combination of reduced tolerance to hangovers and bleary eyed mornings, burgeoning responsibilities, a vague post-alcohol guilt and, basically, reduced social opportunities for drinking. Some people take this as an opportunity to stop altogether, perhaps they never really enjoyed drinking anyway, and some simply don’t trust themselves to drink, perhaps finding it pulls them into oblivion a little too quickly.

On the other hand many people are not quite ready to say goodbye to alcohol just yet and enter the international waters of ‘moderate drinking’, where safe passage is not always clear. As already mentioned, discussion in the media about the risks - and even benefits - of alcohol is chaotic. Public health guidance can be vague, producing statements such as ‘there is no safe level of drinking’ without being clear exactly what this means, and this can come across as a touch puritanical. I have full sympathy with public health officials who have the Herculean task of continually having to encourage people to stop doing things they enjoy, but such statements are liable only to elicit a certain resentment at being made to feel guilty for enjoying one of life’s few remaining simple pleasures.

Furthermore, such statements are misleading, because there is no safe level of anything, with the exception of breathing perhaps. Certainly there is no safe level of sugar consumption, or driving, or stress due to working too much. Really, to say that there is ‘no safe level of drinking’ is a clever evasion, the statement least likely to land anyone in trouble, but it doesn’t really tell us anything or be of use to anybody who actually drinks. To this end I think it would be more realistic to adopt a ‘better drinking’ approach, as in; how to turn a potentially harmful habit into something that can be enjoyed, with minimal harm to your overall health. We will see that this is in fact entirely possible, but to help understand why it is helpful to look in a bit more detail at how alcohol is processed in the body.

Alcohol Metabolism

Among the many erroneous health beliefs that I used to entertain was that it was possible to sweat alcohol - or the remnants of it the next day - out of the body. Another was that if I drank enough water during a night out I would be able to dilute the alcohol in my bloodstream and slow its effects (true) and therefore pee it out before it could cause any harm (false). As it turns out, less than 5% of alcohol is excreted intact in urine, sweat or breath and little seems to alter this (though there is evidence that something called ‘isocapnic hyperventilation’ can increase ethanol clearance four-fold, which potentially hold some application in acute intoxication but seems practically challenging, not to mention unpleasant).

A more widespread myth that I often see online is that alcohol stays in the system for many months, even years. Like a lot of clickbait this is spurious but has a small grain of truth. A minuscule amount, less than 0.5%, of alcohol is processed via ‘non-oxidative’ metabolism, in which the alcohol molecule is incorporated into larger molecules called fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) which do linger for a long time in the body. This seems to be more a product of binge drinking, and accumulation of FAEEs is implicated in pancreatitis. However, in moderate drinking the body uses a safer metabolic pathway, the same one that we evolved when our ape-like ancestors came down from the trees and started eating boozy fruit.

ADH and ALDH

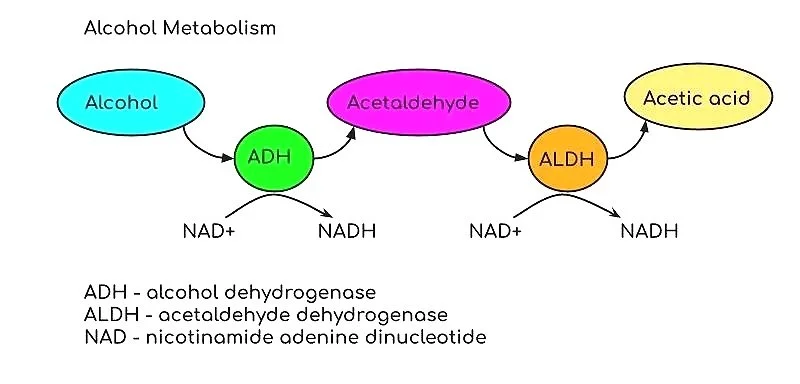

Around 95% of the alcohol we ingest is processed via oxidative metabolism. This involves two steps: conversion of alcohol to acetaldehyde, and then acetaldehyde to acetate, a.k.a acetic acid. Alcohol is broken down by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) which is abundant in the upper GI tract and liver (where it comprises about 3% of the soluble protein). It breaks down alcohol with the ‘reduction’ of the molecule NAD+ to NADH.

Alcohol is broken down to acetaldehyde then acetic acid mainly in the gut and liver. Although the rate of alcohol elimination is roughly 1 unit per hour, factors such as food can have a significant effect on metabolism.

Other than it being a sugar, alcohol is non-toxic, as is acetate. It is the intermediary metabolite acetaldehyde that is chiefly responsible for the harmful physical effects associated with drinking (we’re ignoring behavioural consequences for now). Acetaldehyde is converted rapidly, within minutes, into acetate by the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) found primarily in the liver. Recent research has shown that up to 30% of acetaldehyde can be excreted by the liver in bile, which is the then processed by gut ALDH, so increased bile flow can also increase alcohol elimination rate (AER).

The Variants

Not everyone processes alcohol the same. Genetic variants can affect the expression of enzymes like ADH which lead to a faster breakdown of ethanol to acetaldehyde. Such a variant is common in people from east Asia and around 25% of people of Jewish descent. Perhaps better known is the variant of ALDH - ALDH2*2 - which is common in certain Asian populations (Han Chinese, Korean and Japanese) and is virtually inactive, leading to a build-up of acetaldehyde after drinking, resulting in the notorious ‘flush reaction’, involving headache, nausea and increased heart rate and which can be severe enough to constitute a functional ‘allergy’ to alcohol. (Perhaps as some consolation, the incidence of alcoholic cirrhosis is reduced by 70% in ALDH2*2 carriers.)

It is also possible to intentionally disable ALDH with certain medications like disulfram, sometimes used by heavy drinkers to make themselves functionally allergic to alcohol, and certain antibiotics like metronidazole which knock out ALDH. There doesn’t seem to be a way to significantly increase ALDH activity, though there is a drug called metadoxine which seems to be able to do this to some extent. In any case ALDH works quickly enough, but the ‘rate-limiting factor’ is the availability of the enzyme - the liver only has so much ALDH at any one time and can’t speed up supply. The enzymes reach a saturation point after less than one drink and after then it is very much a case of ‘one-in, one out’ when it comes to alcohol metabolism, that is to say, alcohol is processed at the same rate regardless of how much is in the bloodstream, a phenomenon known as zero-order kinetics.

Other Pathways

Not all alcohol is cleared via the ADH-ALDH double act. In the brain alcohol is metabolised via an enzyme called catalyse. In heavier drinking the liver recruits another class of enzymes called the cytochrome-P450s (CYP450) to deal with the excess. CYP450s are the workhorse of the body’s detox system, involved in the breakdown, among other things, of medications such as opioids like morphine or codeine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and most anti-depressants like SSRIs, which is why, in general it is safe to drink – within reason - while taking these medications as they are not competing for the same enzyme - though it’s worth noting that alcohol and NSAIDs can both cause gastric irritation.

Normally CYP450 plays a minor role in the clearance of alcohol but with chronic, heavy drinking the body increasingly relies on CYP450s which, when metabolising alcohol, produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS) which cause tissue damage, mainly in the liver. When we talk about ‘oxidative stress’ we are chiefly talking about the effects of the (not-so-friendly) ROS. Anti-oxidants can help mitigate the effects of ROS, and some research has shown antioxidants such as S-AME, NAC, folic acid and vitamin C can help protect liver cells.

The toxicity of acetaldehyde is mainly in that it provokes inflammatory molecules and interacts with certain proteins to form adducts which interfere with normal cell production. For example, adducts can form on the surface of red blood cells, causing them to enlarge (called macrocytosis), or in those involved in iron storage, leading to high iron levels, both of which are often seen in heavy drinkers. Adducts can also form with collagen proteins on the skin or in certain cells in the liver and even the brain. Reducing the toxic byproducts of acetaldehyde seems to be really a matter of both reducing acetaldehyde build-up and increasing its clearance. The question naturally arises of how.

Food: The Drinker’s Friend

The most reliable way to do this is with food. We’ve seen how food can increase first-pass metabolism by as much as 50%. Eating also naturally slows down the rate of alcohol ingestion - we tend to drink a lot slower with a plate of tapas or other nibbles in front of us. Interestingly, food also increases the rate of elimination of alcohol and acetaldehyde when already in the systemic circulation. Having something to eat increases ethanol elimination by as much as 33-50%. Studies vary on which type of food is better at this, but one showed that a varied meal of fat, protein and carbohydrates led to an increased elimination rate of 45%. Fructose, normally a dietary villain, seems especially effective at speeding alcohol elimination, perhaps accounting for some people craving sugary food after drinking, or the custom apparently common in Russia of eating fruit while drinking. The ‘fructose effect’ is chiefly due to fructose metabolism converting NADH back to NAD+, which is then used by ADH and ALDH. Other ways in which eating is thought to speed up ethanol elimination are that food increases the activity of ADH, increases blood flow to the liver and promotes bile flow.

The Hangover

A lot has been written about hangovers. No decent work of literature is complete without someone at some point experiencing a catastrophic hangover. There is also a wealth of articles about how to treat hangovers, ranging from the standard ‘hydrate and rest’ advice to more colourful formulations like Anthony Bourdain’s tempting ‘aspirin, cold coca cola, a joint and spicy Szechuan beef.’ Hangovers are due to a constellation of insults to the body. Causes include gastric irritation and sometimes a stomach that refuses to empty thanks to pylorospasm, at times culminating in an unfortunate expulsion the other way*. The dehydration is thanks to alcohol inhibiting vasopressin, or anti-diuretic hormone (ADH). ADH tells the kidneys to reabsorb water back into the body, so its inhibition leads to water and salt loss in urine. Poor sleep results from alcohol inhibiting REM sleep and also a rebound of adrenaline levels, usually around 2 in the morning, often combined with the diuretic effect. Then there is general inflammation triggered by oxidative stress from acetaldehyde production and of course the aforementioned anxiety resulting from too much glutamate and too little GABA in the nervous system. Fortunately in most cases the physical effects wear off by 24 hours.

With regards to what drinks are worse for hangovers, generally it is a matter of quantity rather than quality, but drinks rich in congeners, which add complexity and flavour, and are found in wine or whisky, can result in especially severe hangovers. Why? Certain congeners like quercetin-3-gluconaride found in wine inhibit ALDH, leading to accumulation of our old fried acetaldehyde. On the other hand wine is also rich in flavinoids which have anti-oxidant properties.

* Studies have shown that alcohol concentrations above 30% tend to cause the pyloric sphincter at the exit of the stomach to clench shut, perhaps sensing a potential toxin.

How Much Is Safe?

The harms of heavy, chronic drinking are well established and the consequences are usually obvious both mentally and physically. However, when it comes to light-to-moderate drinking the long-term risks are not that easy to determine because this type of drinking doesn’t usually produce conditions like liver cirrhosis. For this reason research tends to focus on health outcomes like cardiovascular disease or dementia and then compares a population of drinkers to non-drinkers in a retrospective study; that is, a study that takes a group and looks back over the past decades and comparing rates of disease among self-reported drinkers and abstainers. Researchers then try to pick apart the data, trying to remove ‘confounding factors’ such as economic status, to tell as far as possible if alcohol is associated with a higher risk of developing, say, dementia or having a heart attack, compared to not drinking.

How Much Is in a Drink?

Scientists tend to measure alcohol in grams. In the US a standard drink contains 14g of ethanol which is equivalent to a 12 oz can (354mL) of 5% ABV beer, a 5oz (148mL) glass of 12% wine, or 1.5oz (44mL) spirit at 40%. In the UK we tend to use the unit, which contains 8g ethanol. Calculating how many units you’ve drunk is fairly straightforward:

Unit/s = % ABV x mL divided by 1000

So a 330mL can of 5% beer is 5 x 330 / 1000 = 1.65 units, or;

A pint of 4% beer is 4 x 568 / 1000 = 2.3 units

Of note, there is no fixed ‘standard drink’. In the UK it is usually 1.25 units. In the US it’s 1.75 units. To make matters more confusing it is not always clear which a study is using, so for the sake of convenience I am generalising a drink to around 1.5 units, which is roughly a small can of beer or glass of wine.

The J Shaped Curve

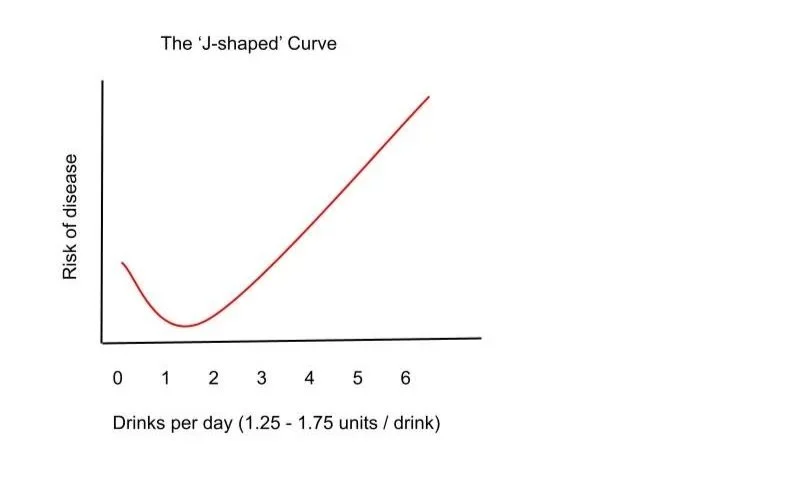

The media obsession with the hazards of moderate drinking are, of course, chiefly driven by the need to get a target audience clicking on articles. Anything that provokes anxiety is a tried and tested way to do this, and there is also a lot of mileage to be had out of recycling contradictory messages. So we are informed that moderate drinking is protective of health and then also that there is ‘no safe level of drinking’. Which is it? Most large-scale studies and meta-analyses over the past few decades show similar findings; that 1-3 drinks a day carries a low risk for cardiovascular events like strokes or heart attacks, as well as metabolic disease like diabetes and neurological conditions like dementia. After 3 drinks a day the risk starts to increase and after 4-5 per day this rises further. Interestingly - and this seems to be the cause of much controversy - complete abstinence tends to show a slightly increased risk of these diseases, leading to the classic ‘J-shaped' pattern.

Many large scale studies over the past two decades show a slightly reduced risk among light to moderate drinkers compared to non-drinkers for diseases like heart attacks, type 2 diabetes and strokes. The risk then increases.

There is no clear idea why this should be so. Are moderate drinkers more relaxed? Does wine or beer contain protective compounds? Do moderate drinkers live otherwise healthier lifestyles? Do they exercise more? Are teetotallers more likely to have other health problems? Periodically research will attempt to debunk this J-shaped model, leading to the ‘no safe level of drinking’ pieces. These often use very sophisticated genetic modelling and show that drink doesn’t actually prevent disease - effectively flattening the first part of the ‘J’. The debate is ongoing, but perhaps it may not be that important. For one, I can’t imagine any non-drinkers will start drinking to reduce their risk. Also, for most light-to-moderate drinkers their main concern is whether drinking is going to harm them long-term, and the studies consistently seem to say the same thing: probably not.

Two Types of Risk

A crucial distinction with any study that looks at risk is between relative and absolute risk. Absolute risk can be thought of as the ‘real world risk’, taking into account the overall prevalence of a given health problem. For example, a study might say that doing X doubles your risk of D. In other words X doubles your risk relative to not doing X. However if D only occurs in one in a million people, the absolute risk has only risen from 1 to 2 in a million.

As an illustration, a 2018 study in the Lancet into the global impact of alcohol consumption, showed a steadily increasing relative risk of alcohol-related health problems after just one drink (1.25 units) a day and led to the conclusion that there was ‘no safe level of drinking’. However the scientists behind the study then released their findings using absolute risk and this gave the findings a different complexion: with 1 drink a day the absolute risk rises only 0.5%

“…meaning 914 in 100,000 15-95 year-olds would develop a condition in one year if they did not drink.…and this goes up to 918 in people who have a drink a day.”

This goes up to a 7% absolute risk for people who drink two alcoholic drinks a day (977 people in 100,000 developing an alcohol related health problem) and goes up to 1252 people in 100,000 with 5 drinks a day. Statistics expert David Speigelhalter puts this into further context; ‘upon closer inspection (the data) still shows 1600 people would need to drink 32 bottles of gin in a year for one person to develop an alcohol related health issue.’*

In any case, most people are aware on some level when they are drinking too much. Getting from here to a place where one is no longer dependent on, or anxious about, drinking can seem like a daunting prospect, but an important step is to take away questions of moral judgement. The fact is that we have evolved to seek pleasurable things, or things which take away the stress, boredom, worry and irritations of life, and alcohol not only does this effectively and quickly but usually tastes nice too, and is often associated with other enjoyable things like food and company. In this respect it is perhaps better to view alcohol as a medicine, with its own risks and benefits, and find a level of risk one is comfortable with. For some heavy drinkers - the oblivion-destructive drinkers - they have little choice but to stop, but for the lighter, less dangerous drinkers complete sobriety may not be realistic or even that much better for them. Of course, there is a lot to be said for being sober, or periods of abstinence, and it can feel very satisfying to know that you don’t need to drink, that it really is a choice. It’s also refreshing to wake up relatively clear headed. An ‘alcohol-fast’ of the Dry-January type may not quite bring the life-changing clarity one hopes for, but at least it clears the skin up a bit. All of which, dare I say, we can look forward to after the festive season.

Below are a selection of studies which support the hypothesis that light-to-moderate drinking can confer some reduction in risk of certain diseases, or is at least relatively okay in terms of health

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31310-2/fulltexthttps://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.d671

Recent advances in alcohol metabolism: from the gut to the brain, MR Goldman, M Molina-Castro et al. Physiol Rev. 2024

GABAa receptors and alcohol, I A Lobo & R A Harris, Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 200

https://alcoholchange.org.uk/alcohol-facts/fact-sheets/drinking-trends-in-the-uk

Sugar: The real reason we put on weight, and how we can get back control of our health

The global food production system, driven by market forces, has resulted in adults being exposed to around 1000 surplus calories a day. Yet we still blame people for getting overweight. Chronic exposure to sugar is driving metabolic disease and obesity. Here is what we can do to fight back, eat better and gain control of our health.

Alarm Bells

It is customary when talking about weight to begin with a series of alarming statistics, and so we’ll proceed accordingly. According to the World Health Organisation in 2022 one in eight people globally were obese - including 160 million children and adolescents - and around 43% of adults globally were overweight. Worldwide, adult obesity has doubled since 1990 and adolescent obesity has quadrupled. At this point we usually talk about an impending ‘obesity epidemic’ set to ruin civilisation. We ask who is responsible and all too often point the finger at the individual, caught frozen with a glazed donut in hand. We then ask what we can do about it, and whatever we propose - injections, more exercise, food labels… -it is hard to escape a slightly defeatist tone to the whole issue. As if we were doomed by our own insatiable appetites, and the best we can hope for is to suppress them for a while.

Weight remains a topic fraught with misunderstanding - despite so much media noise - and when we don’t understand something we tend to give up on it, or wait in hope for someone to fix it. We also develop assumptions which aren’t true. For instance, when analysing the causes of obesity we will see that it makes no sense to blame people for being overweight, and if we take a closer look at the ’obesity epidemic’ we see that actually obesity is not really the problem at all, and by fixating on it we are losing sight of a far bigger problem. But perhaps most importantly, losing weight and getting healthy doesn’t have to be a struggle, or worse, a penance. In fact getting healthy simply requires a switch from trying to satisfy our appetites to satisfying our hunger, in ways that are enjoyable.

Before taking a dive into this, it is useful to go back to the very basics and ask some rudimentary questions like, what exactly makes us put on weight in the first place.

Liberating Carbohydrates

The history of agriculture could be seen as a series of advances which have allowed for higher yields of calories relative to the effort put in. There has always been a pay-off between the amount of energy spent getting and digesting food and the amount of calories ultimately used or stored. For around 2 million years our paleolithic ancestors invested a lot of time and energy in hunting, gathering, preparing, chewing and digesting food. They lived off meat, fish, nuts, vegetables, mushrooms and fruits. Starch - carbohydrates - such as found in roots or cereals was locked within fibre and took effort to release. Then came the development of agriculture around 10,000 years ago which eventually saw carbohydrates become the main staple of our diet. Starch has now been refined to such a degree that, with the exception of wholemeal bread etc., we have easy access to essentially pure carbohydrates, that is glucose, with very little investment needed to digest it. Put simply, we no longer have to work for our calories. It would be tempting to see liberation of carbohydrates as the main reason why nearly half of all adults globally are now overweight…and yet only a small fraction of the glucose we ingest actually gets stored as fat. Something else must be doing it.

Around 300 years ago we began refining sugar, mainly from cane or beet and more recently from maize in the form of high fructose corn syrup. Sugar is a pairing of a glucose and a fructose molecule, around half and half. Once ingested, the glucose and fructose are separated very quickly in the gut. The glucose is used quickly for energy or stored as glycogen. All of our cells require glucose to function. It is vital to life. On the other hand fructose makes sugar taste sweet but beyond this has little nutritional value other than it’s conversion into fat, which was useful when we faced periods of scarcity, such as winter. Our Stone Age ancestors probably ingested around 15g of fructose a day, plus a lot of fibre in the fruit they got it from, and for the first few hundred years of refined sugar’s iniquitous history, it was not consumed in great quantities, being too expensive for the ordinary person. But by 1977 our diet contained around 37g per day and by the 2020s we ingest on average around 75g of fructose a day.

Hiding In The Open

Why is there so much sugar in our diet? It is tempting to say that we eat so much sugar because we like it, but like many of our common sense assumptions, while not altogether wrong, it misses the mark. Sugar by itself isn’t that nice. If offered half a bowl of pure sugar, most people would struggle to eat it, but mixed into ice cream and the struggle disappears. Few people could drink eight teaspoons of sugar in a glass of water, but mixed with citric or malic acid, as with orange or apple juice, or with salt and other flavours as in cola, and we’ll easily gulp it down.

The primary role of sugar in our modern diets is as an additive, and this is the real reason we now ingest so much. As an additive sugar is extremely profitable. It makes us more likely to buy that particular food or drink. It also acts as a cheap preservative, making food easier to transport and store. Conversely fibre is less palatable and more perishable, so has gradually found its way off the supermarket shelves. It is this combination of low-fibre and high-sugar that is characteristic of ultra-processed foods. Most of us eat some form of ultra processed food daily, some more than others. Over the months and years this exposure to ‘hidden’ sugar leads to weight gain, or metabolic disease, or both.

To see how this happens we need to unpack a little of what sugar does in the body.

Glucose Metabolism

Carbohydrate (glucose) metabolism: most glucose gets used up within a few hours, but around a fifth goes to the liver (and some to the muscles) for storage as glycogen.

The human body has been described by the writer Gary Taubes as ‘a busy chemical plant transforming and re-directing energy’. Every process necessary to life - from movement to thinking, to cell division to digestion - requires a transfer of energy, and the main molecule responsible for this is called adenosine-triphosphate (ATP) which in turn gets ‘refreshed’ by glucose. Most of the glucose we eat gets sent to the organs, muscles and tissues to be used in this way, but around a fifth goes to the liver where it is stored as glycogen (muscles also store glycogen). The important thing to note here is that glycogen is non-toxic. You can carb-load as much as you like but the glycogen won’t do any damage - it simply sits there waiting to be broken back down to glucose when needed. The second point is that only a very small amount of the glucose is converted by the mitochondria (the power houses of the cell) to triglycerides and thence to fat, so one would need to eat a lot of glucose to actually put on weight. With the exception of sugar, carbohydrates do not in themselves make us fat. However they do make it hard to lose weight once it’s on, because they are such a calorie-dense source of energy, and too many carbs can blunt our sensitivity to insulin. So while glucose by itself is okay, when twinned with fructose it sets up processes that make us gain fat.

Sugar Metabolism

Unlike glucose, all of the fructose we ingest is metabolised by the liver. It doesn’t provide energy for tissues. (Sweet tasting energy gels often used by runners often use dextrose or maltose which are chains of glucose molecules.) The mitochondria of the liver then has to metabolise the fructose. The small amounts of fructose ingested by our paleolithic ancestors weren’t an issue for the liver, and in any case the plentiful fibre slowed its absorption. However the modern way of ingesting large boluses of fructose with little or no fibre quickly overwhelms the mitochondria, leading to high triglyceride and fat production. Moreover this type of fat tends to be deposited around the internal organs, so called visceral fat, which is more harmful than the more spread out subcutaneous fat.

Alcohol is (Regrettably) Sugar

It is worth noting that another common sugar that is metabolised in the same way as fructose is alcohol, which is why seasoned drinkers normally develop a beer belly. In fact a standard can of beer carries roughly the same sugar hit as a can of soda. A few differences are that the brain is actually able to use alcohol as a source of energy. Also in terms of general use, alcohol is self-limiting; you can only drink so much before you have to stop, whereas with sugary drinks one can potentially keep drinking all day. Also soda often contains salt and caffeine which boost their addictive quality and with some justification soda has been called ‘alcohol for children’.

At this point we can mention the growing condition of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), also known as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MDASLD) or ‘sugar belly’, depending on how diplomatic you want to be. Historically a fatty liver was the result of many years of alcohol misuse. but we are now seeing more NAFLD which can progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatosis (NASH), a precursor for cirrhosis. The culprit is almost certainly high sugar consumption. Since 1980 cases of NAFLD and NASH have doubled alongside fructose consumption. In the United States an estimated 6 million have NASH and it is the third leading cause of liver transplants. Around 31% adults and 13% children are estimated to have NAFLD in the US. Depressing though these figures are, the good news is that NAFLD is to a significant extent reversible with the right measures, i.e. cutting sugar from the diet.

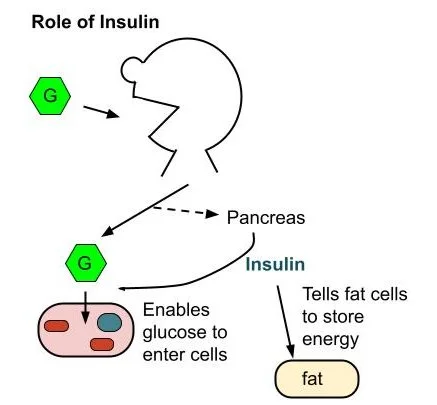

The Insulin-Leptin Double Act

Hunger is one of our fundamental drives and we have evolved feedback signals to both motivate us to find food and tell our bodies when we have had enough. These feedback loops are mediated by our nervous system - such as our ‘rest and digest’ parasympathetic system - and hormones. Two of the most important hormones are insulin and leptin. Insulin is secreted by the pancreas after we eat. It plays the crucial role of enabling glucose to enter cells. Another role of insulin is to tell the adipose cells to store energy in the form of fat. The general rule with regards to good metabolic health is; the less insulin needed, the better. If the cells are sensitive to insulin then less will be needed and - because insulin tells adipose cells to store energy - less fat will be laid down.

Insulin allows glucose into cells and tells fat cells to store energy

However, with chronically high glucose intake - for instance if we are snacking - insulin remains elevated to try to mop up the excess glucose. Furthermore with refined carbs like sugar we get spikes of insulin, and the subsequent crash leads to lethargy, brain fog, and the craving for more. Over time raised insulin leads to reduced sensitivity to it as our body ‘down-regulates’ the insulin receptors, leading to insulin resistance. The combination of high blood glucose and insulin resistance is characteristic of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

It is worth mentioning in passing two exceptions when evolution ‘says’ it’s better to gain weight; puberty and pregnancy. In both cases our body is trying to gain weight and hormonal shifts occur that make us insulin resistant. This may account for why adolescents are more at risk of obesity. On the other hand, it is important that teenagers know that a bit of extra weight at that age is to be expected, and will most likely come off again so long as they avoid a lot of sugar. This is also why some women develop gestational diabetes which normally reverses after the baby is born, though is also a time of risk where many mums put on weight which they find a challenge to lose later (especially when coupled with the demands of parenthood).

Leptin, released from fat cells, tells our brains we are full.

Leptin is the second part of the act. When fat cells start to fill up they quickly release leptin. The role of leptin is essentially to make sure that we don’t eat too much, as being continually full is not a useful evolutionary strategy, we need to go out and get things done. Leptin travels via the bloodstream to the brain where it acts on the hypothalamus. It is a satiety signal which says we’re not hungry anymore. It also tells the brain that we can now engage in metabolically expensive activity. In other words, we can burn energy. This leads to activation of the sympathetic ‘fight-flight’ nervous system, which manifests as fidgeting ‘nervous’ activity. This whole insulin-leptin feedback loop is known as ‘anorexigenesis’ - that is, eating provokes a cascade of hormonal responses which then reduce our appetite. Now we’ll see what happens with chronic sugar exposure:

Chronically high insulin blocks the satiety signal, so we feel hungry despite being full.

The Sting in the Tail

As we’ve seen, with a chronically high intake of glucose insulin becomes less effective at unlocking the cells, so we also wind up with more circulating insulin. The increase in fat storage also leads to more leptin being released. But here is the sting in the tail - insulin blocks the action of leptin on the brain. This leads to the paradoxical effect where, even though we have too much fuel, the brain is not getting the satiety signal - it ‘thinks’ that we are hungry and don’t have energy to burn. This manifests as an increased appetite and reduced drive for physical activity. This is ‘orixogenesis’ and is the flip-side of the normal process previously described. Sugar therefore presents a triple-whammy to our bodies: 1. The pure glucose numbs our insulin sensitivity, leading to higher insulin in the bloodstream, leading to higher fat storage. 2. Fructose gets converted to triglycerides that get stored as fat and 3. Insulin blocks leptin, so we feel hungry, and tired, despite having surplus fuel.

Changing Our Minds About Weight

As the months and years progress, the above process leads to the build up of fat, be it in the liver or around the waist. Why certain people are more prone to putting on weight is down to many reasons. Undoubtedly some people are more prone to putting on weight due to genetic factors, then there are hormonal changes of adolescence and pregnancy; many people simply aren’t in the habit of eating salads, or don’t have the time, and there is a strong statistical association between obesity and ‘lower’ socioeconomic status. Poorer neighbourhoods tend to have more shops selling ultra-processed foods and less branches of Whole Foods. Whatever the reason, it is more accurate to regard metabolic disease, and obesity, as a result of chronic exposure to sugar. When we re-frame obesity as an exposure issue we can locate the real cause; not as some mysterious quality like willpower that an individual is supposed to possess but in the reality of supermarket shelves groaning with refined carbs and sugar-rich products (and governments unwilling or unable to regulate the food industry).

An article in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet summed it up in 2011: “The simultaneous increases in obesity in almost all countries seem to be driven mainly by changes in the global food system, which is producing more processed, affordable, and effectively marketed food than ever before. This passive over-consumption of energy leading to obesity is a predictable outcome of market economies predicated on consumption-based growth.”

Now that we have a clearer idea of what actually causes us to put on weight, we can start looking at how to lose it and stop it coming back on. But before this, we need to unpack a few other common myths:

Eating Fat Makes You Fat - This is an especially stubborn myth. It gained credibility around the 1960s when increasing numbers of men in affluent countries were succumbing to coronary artery disease. Studies at the time showed a correlation between high fat diets and increased cholesterol in the blood. This was convincing enough that by the 1980s the US and UK governments issued dietary guidelines and doctors began promoting low-fat diets. Yet rates of cardiovascular disease continued to climb and it was far from proven that fat in the diet led to fat in the bloodstream. We know that the liver synthesises cholesterol. In fact, if you eat more healthy fats like omega-3, the liver responds by producing less cholesterol. Healthy fats are also too buoyant to stick to the lining of blood vessels. Also, how to explain significant outliers like France where a fat rich diet accompanies low rates of heart disease? Fat is calorific: it contains around twice as much energy per gram of carbohydrate.Yet unlike sugar fat promotes early satiety and is non addictive so we tend to eat less.

Eventually the fat hypothesis was debunked. In 2008 studies by both Oxford University and the UN Food & Agricultural Organisation found ‘no probable or convincing evidence’ that high dietary fat causes heart disease or cancer. The alternative hypothesis, that perhaps it was sugar causing heart and disease, was raised in 1980 by the UK doctor and professor John Yudkin, which he outlined in his classic book ‘Pure, White and Deadly’. Unfortunately not only was he ahead of his time, but he was also going against the prevailing medical orthodoxy, not to mention the sugar industry. He was smeared in publication and denied work. Only recently has he been vindicated.

Fat is Just Storage Tissue - Adipose tissue is far more than a storage sink for excess energy. It is also active endocrine tissue, continually secreting hormones such as leptin and oestrogen. It also is pro-inflammatory, which likely plays a role in chronic pain. Again, losing adipose tissue can go a long way to remedying conditions like chronic inflammation or polycystic ovarian syndrome.

A Calorie Is A Calorie - An authority on sugar is the paediatric endocrinologist Robert Lustig, whose lecture ‘Sugar: The Bitter Truth’ now has a few million views on YouTube. One of his central points is that calories are not the same. The body has to invest more energy in digesting certain foods. Protein takes around twice as much energy to metabolise compared to carbohydrate. The speed at which we digest calories is also important. Fibre plays a crucial role in slowing the release of carbohydrates, which is why fruit and vegetables are okay to eat (a note of caution - certain fruits like grapes and bananas actually release sugar very quickly). An almond contains around 160 calories, but only 130 get absorbed due to the high fibre. Fibre is very much the antidote to refined carbs and sugar, the more the better.

Obesity Is The Problem - Obesity is in fact a result of the problem but not the cause. The real issue is metabolic dysfunction, which leads to conditions like type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver etc. Around 20% of people with obesity have healthy metabolisms. Even though they are at greater risk of metabolic disease there are still far more people of normal weight who are at risk and who will eventually strain our health and social systems.

Getting Sick From Sugar is a ‘Behaviour’ - While it is tempting to blame the individual for ‘getting fat’, this misses the point. People don’t choose to become sick or overweight. They become so due to metabolic processes which have been deranged by years of covert exposure to refined carbs. What may seem like small amounts of daily sugar - a breakfast orange juice or bowl of granola, a bun or few biscuits in the morning, a sweet latte or lunchtime smoothie with a meal deal, etc. - over the months and years have a cumulative effect. Many of us can’t understand why we gradually put on weight despite what seems to be a healthy diet.

The Limits of Lifestyle

There is a view that we ought to stop talking about obesity altogether due to its powerful stigmatising effect, and that we need to do what we can to accommodate larger people and even stop preaching the lifestyle mantra of ‘eat less, exercise more’. The findings of an analysis recently published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) stated: ‘Rigorous evidence has indicated that lifestyle interventions, which involve a change in behaviour with a focus on restriction of energy intake and increased physical activity, have little to no effect on sustained weight loss.’ (BMJ July, 2025). The overall conclusion seems to be that simply telling people to eat less and exercise more is not effective.

That said, ‘lifestyle intervention’ can mean a lot of things. It’s not surprising that people don’t respond to advice alone, but there’s more to lifestyle medicine than just telling people what they already know. There are many community and city-wide measures that can be taken, from Park Runs, to healthy school meal campaigns, to ‘active transport’ initiatives, from increased cycle lanes and cycle-to-work schemes, to the legendary Ciclovias in South America, that offer a different future to business as usual, an alternative to the view that the best we can hope for is the mass roll out of medications to deal with obesity and metabolic disease.

What is the role of exercise? While exercise does not usually lead to weight loss directly - the body is just too efficient - exercise will increase good weight, that is muscle and bone density, as opposed to bad weight like visceral fat. Also, the more dense the muscle, the more mitochondria, which means that it can burn fuel a lot more effectively, even while at rest. Plus it increases sensitivity to insulin, which counteracts high blood insulin levels and the ‘numbing’ effect it has on leptin. Exercise increases our perception of how much we can exercise; the more you do the more you feel you can do.

Do Diets Work?

In the same edition of the BMJ mentioned above, another analysis of 99 randomised control trial showed that intermittent fasting (in particular alternate day fasting) produced ‘significant weight reduction compared with ad libitum diets’ (i.e. eating when you want). It also showed that ‘continuous energy restriction’ of 30% calories also produced weight loss though the effect was generally quite small 2-4kg, and that adherence waned over a year to around 9.5% restriction. And while intermittent fasting is a very effective weight loss tool again adherence seems to wane with around 22% still following the regime after a year.

If there is a common theme in these findings, it is that while diet or fasting does lead to weight loss, after a period of time in most people the weight comes back on. There are two important points to be made with regards to this. The first is that, as we have seen, there is more to health than just losing weight. You may not necessarily shed a lot of kilos by fasting and dieting, but most people report feeling a lot better in any case, they may have greater muscle density, and it improves metabolic health. Secondly, it is inaccurate to conclude that calorie restriction doesn’t work. The evidence shows that it does, but just that it is difficult to sustain.

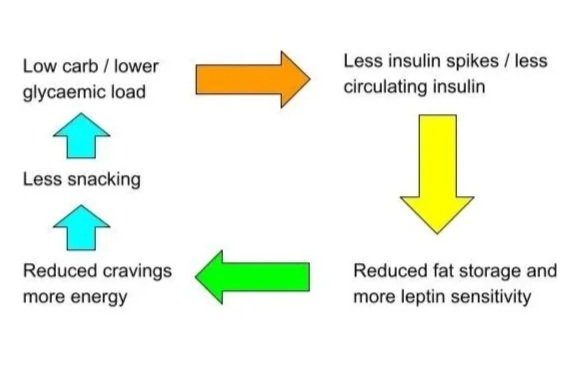

A sustainable way to achieve a calorie deficit is to cut back on calorie-dense carbohydrates. However carbohydrates are part of a healthy diet and do not in themselves make you put on weight. Certain populations like the legendary Okinawans eat a lot of rice but don’t generally get overweight. The difference is that these cultures are physically active and also eat a lot of protein and fibre-rich vegetables. Remember that fibre effectively slows down the absorption of glucose so carbohydrates with fibre are far better, so aim for carbohydrates with a low glycaemic index, such as wholemeal. Over the months this sets up a positive feedback loop:

Regarding the low-fat vs low carb debate, numerous studies now show that low-carb diets are as, and in many cases more, effective than low-fat diets in losing weight. Overall the evidence tells us that a sustainable diet to maintain a healthy weight and metabolism amounts to: more protein, more (good) fat, more fibre, less simple carbs. Some diets - such as keto - go so far as advocating cutting simple carbohydrates completely. While no doubt effective there are many specialists who are sceptical about removing such a vital energy source from the diet and in any case for most of us a zero carb diet is not sustainable.

Turning Down the Food Noise: Appetite Vs Hunger

There has been a lot of interest recently in the phenomenon of ‘food noise’, that nagging persistent craving for something to snack on. This is likely a combination of psychological and organic factors, such as the blunting of the aforementioned insulin-leptin pathway. Sugar is also weakly addictive as it leads to a dopamine spike - before even the sugar enters the bloodstream - and anything that triggers a rapid release of dopamine quickly becomes addictive.

Another way of understanding food noise was set out by John Yudkin in Pure, White and Deadly in which he points out the difference between hunger and appetite. Hunger is a physiological need for calories. On the other hand appetite is what makes us eat even though we don’t need to. Hunger can be satisfied because of our organic feedback mechanisms, whereas appetite is the beast that gets hungrier the more we feed it. We could simplify this further: Healthy food satisfies our hunger, we seek rubbish food to satisfy our appetite. When we crave food, it is rarely a carrot or handful of peanuts we reach for (and which would easily keep our hunger at bay). The food industry is geared towards provoking our appetite.

In order to curb our food noise the first step should be pretty obvious - radically cut down sugar. The World Health Organisation recommends less than 50g a day. A general rule of thumb would be less than 10 tsp a day for adults and less than 5 tsp for children. Some will find this more difficult than others, and to them I would say, don’t despair: Recall that around half of sugar in our modern diets is effectively ‘hidden’; for instance the average breakfast cereal in the US contains or exceeds already the daily sugar limit for children. In eliminating these hidden sugars half the battle is already won. It can be a bit laborious counting the calories and percentages on packaging. A simpler way of avoiding hidden sugars is to prepare your own (or family’s) meals, from as basic ingredients as possible.

The next one-third of sugar comes in soda or fruit juice, including smoothies, so again by replacing this another significant step has been taken. Really children ought to be drinking only water or milk. What about desserts and baked goodies? Traditionally desserts and baked goods are eaten as treats or after dinner and eaten in this way they are far less likely to cause insulin spikes. It is only in the past few decades that sweet snacks have become a mainstay of our diet, and it goes without saying they are loaded with sugar. (For what it’s worth, the only advice I can offer is don’t have them close to hand. If they are in the kitchen, on your desk etc, they will be eaten.) It’s worth recalling that the odd dessert or treat only makes up one-sixth of the sugar we consume. Most of the sugar we now eat is added to what we eat or drink. It isn’t the guilty pleasures ruining our health, it’s the mass produced stuff, and by cutting this out you can reduce your intake by a clear margin.

On a personal note, when I cut my sugar intake the first week or so could be a bit challenging, especially the craving for something sweet after dinner, but the benefits soon far outweighed the odd sugar pang. Within a matter of days my afternoon brain fog lifted and mid morning hunger pangs subsided (I keep a back of nuts and dry fruit in my drawer if I really do need a snack). After a few weeks, fruit began tasting sweet and enticing again and I found it much easier to drink water as it no longer tasted so flat. I also felt far less jittery and reactive. It felt as if I were depriving my brain of the quick and dirty fuel of sugar. I got into the habit of eating a bag of salad from the supermarket for lunch each day, though of course with a nice rich dressing, protein and a crunchy topping. My belly retreated (a bit) and my sleep improved. We’ll see what happens when the days get shorter and the chill winds of October have me eyeing up comfort foods, but for now losing the weight of middle age was nowhere near as difficult as I had anticipated, and I’m in no hurry to go back to the sickly lethargy of sugar just yet.

Resources:

https://phcuk.org/product/real-food-real-budget-flyer-x-100-5-5p-per-booklet/

Truth about calories

https://robertlustig.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Infographic.pdf

The Sugar Conspiracy

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/apr/07/the-sugar-conspiracy-robert-lustig-john-yudkin

Sugar Science University of California

https://sugarscience.ucsf.edu/the-toxic-truth/

BBC BMI and obesity calculator

https://www.bbc.com/news/health-43697948

Dr Unwin’s Infographics / Glycaemic Index

https://lowcarbfreshwell.com/what-is-a-low-carb-lifestyle/dr-unwins-sugar-infographics/

Low Carbohydrate Diet